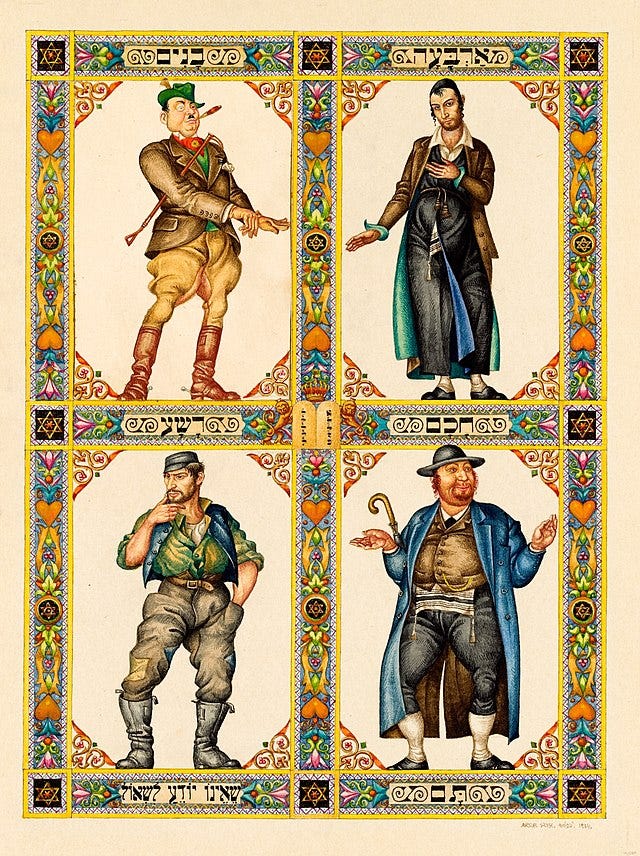

The Four Sons by Arthur Szyk, CCA-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Gimme Some Torah #220, For Your Sedarim

Welcome to new subscriber rpf******!

We are well within the thirty days before Pesaḥ, a time when we are supposed to study and ask questions about the upcoming festival. Today, let’s take a look at a passage in the Haggadah that many Jews of all stripes k…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Gimme Some Torah to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.